Chapter 2 Basic Perceptions about Markets Part II

Most people don’t really understand the marvelous markets we are in. Starting with the efficient market hypothesis, this chapter explains the fundamental characteristics of the markets we live in: randomness, chaos, and time-varying nature, through the construction of stochastic portfolios, statistical tests of randomness, and the successes and failures of machine learning in the markets.

2.3 Are Markets Really Random?

The previous section has demonstrated the power of random positions as a benchmark, and this section will continue to explore whether the market is really random or not. The market randomness tests begin with algorithmic-level definitions, then introduce the NIST suite of statistical tests for randomness and use them on market indices. The results of the tests show that financial markets are neither completely deterministic nor random, but somewhere in between.

2.3.1 Financial Turing Tests

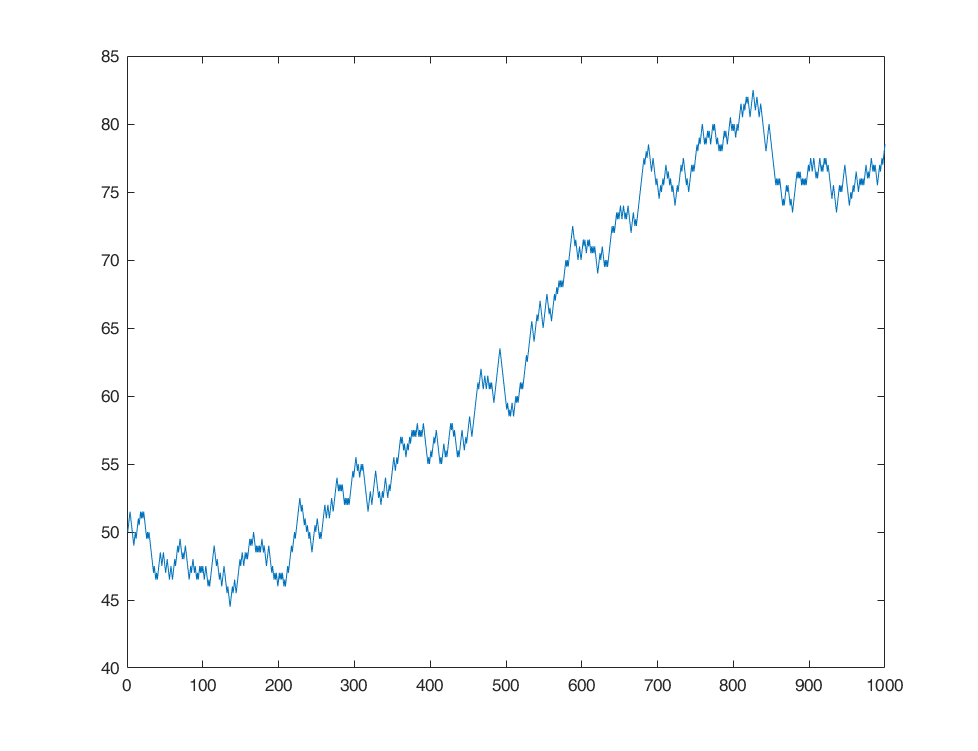

Burton G. Malkiel, professor of economics at Princeton University and author of A Walk Down Wall Street, conducted a test: his students were given virtual stocks initially worth $50, with a daily closing price determined by flipping a coin. If the result was heads, the price would close half a point higher; if it was tails it would close half a point lower. Thus, each day the price has a 50% chance of closing higher or lower than the day before. Malkiel then took the results in chart form to a technical analyst, someone who tries to predict the future by assuming that “history tends to repeat itself”. The technical analyst told Malkiel that he needed to buy the stock immediately. Because coin flips are random, the virtual stock had no overall trend. According to Malkiel, this suggests that the market and the stock may be as random as the coin flip.

The code described above is below:

1 | L=1000; |

The results are shown in Figure 2-8.

If you were not told the truth, would you be confident that you could tell this curve from a bunch of actual stock movements?

This property of financial assets gives rise to the Random Walk Hypothesis of prices (a variant of the EMH), but this hypothesis does not explain how anyone can consistently beat the market. The rest of this section explains the definition of the stochasticity algorithm and how the correlation between local and global stochasticity explains the discrepancy between the random walk hypothesis (known as the random walk) and the market performance of long-term investors. We will also use the NIST stochastic statistical testing algorithm to test actual markets.

2.3.2 Randomness in an Algorithmic Sense

In recent decades, a new cross-discipline between computational and information theory has arisen, called algorithmic information theory. Algorithmic information theory defines different types of randomness, the most popular definition being Martin- Löf randomness, which defines that in order for a sequence to be truly random, it must do the following:

- incompressible. Compression involves finding some lossless representation that uses less information. For example, no ! [For example, the infinite-length dichotomous string 01010101… can be more succinctly expressed as 01 repeating indefinitely, whereas the infinite-length dichotomous string 0110000101110110101… has no discernible pattern, and thus cannot be compressed into an identical dichotomous string. This is equivalent to saying that if the Kolmogorov complexity of a string is greater than or equal to the length of the string, then the sequence is algorithmically random;

- Passing statistical tests for randomness. There are a number of statistical tests for randomness which involve testing the difference between the distribution of a sequence and the expected distribution of any sequence assumed to be random. One way or another, this will be discussed in more detail in the following section;

- Unprofitability. Unprofitability is an interesting concept that simply assumes that if it is always possible to construct a set of profitable strategies on a sequence, then the sequence is not random.

Another interesting distinction between statistical and algorithmic definitions of randomness is between local and global randomness. A sequence is said to be globally random if it appears to be random in the long run, even though parts of the sequence may sometimes appear to be non-random. For example, the sequence 01010100011010101110000000001… looks random, but if we divide the sequence into four blocks [010101] [0001101010111] [000000000] [1…], the first and third blocks are not randomized. Thus, while the sequence exhibits global randomness, it exhibits only partial local randomness.

Relating this distinction to the random walk hypothesis, we should be able to distinguish between the local and global random walk hypotheses. Global random walk suggests that the market appears to be random in the long run, while local random walk suggests that the market appears to be deterministic over time. This worldview is consistent with empirical observations of market anomalies such as value, momentum, and mean reversion, especially when one recognizes that these factors tend to exhibit cyclical behavior. In other words, like the sequence shown earlier, markets exhibit global stochasticity, but local stochasticity breaks down for limited periods of time.

2.3.3 NIST Stochasticity Testing

There are two open source Python versions of the NIST stochastic test, one based on Python 2.66 and the other based on Python 3.4. In this paper, we choose to implement the test based on Python 3.4, and remember to use pip to install the bitstring library first. The following tests and their descriptions are from NIST: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail /sp/800-22/rev-1a/final.

**Discretizing the data

First we must start by binary coding the continuous asset price curve. Discretization involves converting continuous variables to discrete variables, and the most popular method of discretization is split-boxing. Split-boxing categorizes the output from a continuous variable into mutually exclusive sets of boxes, each box representing an interval into which the random variable may fall. Since the range of market returns (our continuous variables) is not known, it is sufficient to categorize them into positive and negative returns ! [ref2], denoted as Bit 1 and Bit 0. To avoid bias, we add a special case for returns exactly equal to 0.0%, which are denoted as the two bits 0 and 1, i.e., the bit string 01:

$$

$b_j = f(r_j) = \left{

\begin{array}{l}

1,\qquad r_i \gt 0.0\

0,\qquad r_i \lt 0.0\

0.1,\qquad r_i = 0.0

\end{array}

\right.

$$

The types of randomness tests are as follows.

1 | def monobit(self, bin_data:str): |

This test looks at the ratio of 0s to 1s in a given binary sequence. Assuming that the sequence is uniformly distributed, the ratio should be close to 1, which means that the number of bit 1s is approximately equal to the number of bit 0s. In our test scenario, since bit 0 means the price of an asset is going down and bit 1 means it is going up, the test checks whether the number of down days and up days in the market are uniformly distributed over time. Failure of the MonoBit Test may indicate that a simple buy-and-hold strategy is quite profitable, since if the market is more likely to go up than down, then simply buying and holding is already a profitable trading strategy.

Test 02 BLOCK FREQUENCY Test .

1 | def block_frequency(self, bin_data: str, block_size=128): |

This test is a general regularization of the Monobit test, which tests the proportion of bit 0s and bit 1s in N blocks of sequence of length M extracted from a given binary sequence. Assuming a uniform distribution of bits, the number of bit 0s and bit 1s should be approximately M/2 per block, i.e., each block is uniformly populated with bit 0s and bit 1s. The test focuses on the probability of a market upturn and a market downturn occurring within a finite window.